Topkapı Palace was not merely the administrative center of a global empire, but also a self-sufficient, enormous city inhabited by thousands. The Sultan’s family, students in the Enderun, the Harem residents, Divan members, soldiers, and countless servants… feeding, clothing, and meeting the needs of this massive population every day required one of the most complex and comprehensive logistical operations in history. The Ottoman palace’s supply chain was the most concrete evidence of the empire’s power, wealth, and organizational genius. This chain was a flawless network, operating with caravans and ships, extending from the fertile lands of Egypt to the cool plateaus of the Balkans, from the silk looms of Bursa to the luxury workshops of Venice. Each link in this network brought a pinch of spice to the Sultan’s table or a silk caftan to his back.

Feeding the Palace: The Logistics Challenge of a Population of Thousands

The permanent population of Topkapı Palace ranged between 4,000 and 5,000 people, depending on the period. However, on special occasions such as holidays, festivals, or receptions for ambassadors, this number could reach tens of thousands. Feeding this enormous population was the biggest challenge at the heart of the functioning of the Matbah-ı Âmire (Imperial Kitchens). Every day, tons of meat, sacks of rice and flour, and barrels of oil and honey were consumed in the palace kitchens. Meeting these needs without interruption was not merely a purchasing operation, but also a state policy.

The palace’s needs were always prioritized. Special purchasing officers, known as “Mübayaacılar,” had the authority to procure the empire’s highest quality products at market prices, and sometimes even through compulsory purchase (iştira). The markets in and around Istanbul were organized to meet the palace’s needs. For example, the best quality flour arriving at Unkapanı was first set aside for the palace, and the remainder was sold to the public. This system was a meticulously planned logistics mechanism that guaranteed the palace would never experience scarcity or shortage.

Traveling the World for the Kitchen: The Matbah-ı Âmire’s Supply Network

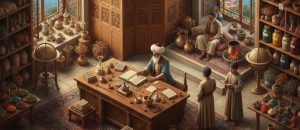

The Matbah-ı Âmire, or Imperial Kitchens, was not just a cooking area but also a gastronomic map of an empire. The ingredients for every dish prepared here were specially brought from the region where that product grew best. This demonstrated how refined the palace’s taste was and how geographically rich its culinary preferences were.

Spices and Rice from Egypt

The importance of the Spice Route was most clearly demonstrated in the Ottoman palace cuisine. With the conquest of Egypt in 1517, the gateway to the Mediterranean for spices from India and the Far East came entirely under Ottoman control. Exotic and expensive spices like black pepper, cloves, ginger, cinnamon, and nutmeg reached Egypt by ship, and from there to Istanbul. These spices not only added flavor to dishes but also served as status symbols and methods of food preservation. Egypt was also the main supplier of high-quality rice, essential for palace pilafs. Meeting the palace’s spice and rice needs through Egypt reinforced the strategic importance of this province for the empire.

Oil, Honey, and Salt from the Balkans

The palace’s needs were not limited to exotic products. Basic ingredients for daily nutrition were sourced from closer geographies within the empire. The Balkans played a significant role in this regard:

- Oil: Olive oil, particularly from Western Anatolia and Thrace, and clarified butter (ghee) from the Balkans, formed the basis of the kitchens.

- Honey: Wallachia and Moldavia (modern-day Romania) were the most important production centers for honey, which was indispensable for the palace’s desserts and sherbets.

- Salt: Salt, vital for food preservation and flavoring, was brought from salt pans in Wallachia and other regions of the empire.

The regular flow of these basic products was an indicator of how efficiently and systematically the logistics in the Ottoman Empire network operated.

Dressing the Sultan: Luxury Fabrics from Bursa and Venice

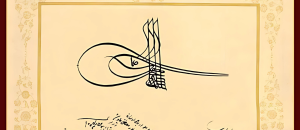

The palace’s needs were not limited to the kitchen. The caftans worn by the Sultan, members of the dynasty, and palace officials were works of art reflecting the empire’s power and wealth. The luxury fabrics used for these caftans also reached the palace through a special supply chain.

Bursa fabrics were the most important link in this chain. Bursa, which became the center of silk trade in the Ottoman Empire and production from the conquest onwards, was renowned for its valuable silk fabrics such as “kemha” (brocade), “kadife” (velvet), and “seraser”. The Ehl-i Hiref organization, the palace tailors, used the finest Bursa silks to sew dazzling caftans for the Sultan. However, the palace’s fabric needs were not limited to Bursa. Luxury velvets and brocades produced in Europe were also imported by the palace, especially through commercial relations with Venice and Genoa. This demonstrated the palace’s global vision in following fashion and luxury.

This massive influx of products arriving in Istanbul from all corners of the empire was gathered in the city’s commercial hubs, the khans and bazaars. The Grand Bazaar (Kapalıçarşı) and the Spice Bazaar (Mısır Çarşısı) played a pivotal role in the Ottoman palace’s supply chain. The palace’s purchasing officers (mübayaacılar) obtained the necessary products directly from these centers or from special wholesale markets (kapan) such as Unkapanı (Flour Quay) and Yağkapanı (Oil Quay).

The establishment of the Spice Bazaar is one of the most concrete examples of this system. Built in the 17th century to generate income for the New Mosque, its expenses were covered by taxes from Egypt. It quickly became the main center for selling spices and other products from Egypt, thus becoming the heart of the palace’s spice supply. These bazaars not only met the palace’s needs but also showcased the vitality of the imperial economy and Istanbul’s position as a global trade center.

Caravans and Ships: The Ottoman Logistics Genius

Two main transportation channels enabled this enormous supply network to function: caravans by land and ships by sea. The logistics in the Ottoman Empire system utilized both channels very efficiently.

- Caravan Routes: Products from Anatolia and the Balkans were transported by caravans consisting of camels and horses. To ensure the safe and uninterrupted flow of this trade, the state built “kervansaray” (caravanserais), which were lodging and security centers, at regular intervals along the main roads. These caravanserai secured the roads, which were the lifeblood of trade, sustaining the logistics network.

- Sea Routes: For bulky products (grains, rice, spices) coming from distant provinces like Egypt, sea transport was much more efficient. The Ottoman navy ensured the security of trade routes in the Mediterranean, guaranteeing the uninterrupted operation of this “grain and spice bridge” extending from Egypt to Istanbul.

The management of this complex network was meticulously carried out by high-ranking officials such as the Kilercibaşı (Head Pantryman) and the Matbah Emini (Imperial Kitchen Steward). Every product’s origin, quantity to be purchased, and storage method were planned in advance. This system was the greatest proof that an empire sustained itself not only by the sword but also by flawless logistics and supply management.