The Art Flowing from the Palace’s Brush to Hearts: Being a Calligrapher and the Subtleties of Calligraphy in the Ottoman Empire

Every eye that steps into the visual world of Ottoman civilization inevitably encounters the magic of letters. From the monumental inscription on a mosque dome to the elegant tughra on a sultan’s edict, from the inscription of a humble fountain to the pages of a handwritten Quran, Ottoman calligraphy is the purest expression of the empire’s aesthetic and spiritual soul. This art is not merely about transferring meaningful letters onto paper, but also about transforming writing into a form of worship with patience, love, and deep spirituality. The saying, “The Quran was revealed in Mecca, read in Cairo, and written in Istanbul,” summarizes the pinnacle this art reached in the Ottoman capital. To be a calligrapher meant undergoing years of arduous training, allowing a divine harmony to flow from the tip of a reed pen onto paper.

A Meaning Beyond Writing: What is Hüsn-i Hat (Ottoman Calligraphy)?

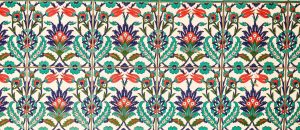

Hüsn-i hat, originating from Arabic, literally means “beautiful writing”. However, this simple definition is insufficient to explain the deep philosophy and cultural significance behind the art. In Islamic civilization, especially under the influence of the prohibition of imagery (tasvir yasağı), the search for aesthetic expression largely focused on geometric patterns, floral embellishments (tezhip), and most importantly, calligraphy. The desire to write the Holy Quran, the word of Allah, in the most beautiful way elevated calligraphy to the status of “the holiest of arts”. Therefore, hüsn-i hat is not merely a product of aesthetic concern, but also a reflection of a spiritual quest, respect for the divine word, and the artist’s inner world. It is “a spiritual geometry emerging through physical tools”.

An Art Forged with Patience: The Training Process of a Calligrapher

One did not become a calligrapher overnight. This art required an arduous training process lasting years, demanding patience, discipline, and dedication perhaps even more than talent. The training of calligraphers was conducted based on a master-apprentice relationship, using a traditional method called “meşk”.

From the First Letter to Ijazah: The Master-Apprentice Relationship and the Meşk System

A young person (talebe) wishing to become a calligrapher would first knock on the door of a respected calligraphy master (üstat) of the time and request to take lessons from him. After the master accepted the apprentice, the training process would begin. This process proceeded with a method known as the meşk system, based on imitation and repetition. The master would write a prayer, such as “Rabbi yessir velâ tuassir, Rabbi temmim bi’l-hayr” (My Lord! Make it easy, do not make it difficult. My Lord! Conclude it with goodness), or individual letters on paper and give it to his apprentice.

The apprentice’s task was to copy this “meşk” written by his master hundreds, even thousands of times, adhering faithfully to the proportions, angles, and aesthetics of the letters. Every week, he would take the papers he had written to his master, who would correct his mistakes with red ink and show him the correct forms. This process would continue for years, from a single letter to the combination of letters, from words to sentences, and finally to writing a complete text. Meşk was not just a technical learning process, but also a spiritual journey where the apprentice disciplined his ego, learned patience, and absorbed his master’s artistic understanding and spirit.

The Approval of Art: The Ijazahname and Its Meaning

After years of meşk, when the master was convinced that his apprentice had reached the maturity to produce his own works and sign them (“ketebehu…”), he would grant him an “ijazah”. The ijazahname was a kind of artistic diploma or license. It was usually prepared as a calligraphy panel on a large sheet of paper, written by the apprentice and approved by the master, who would also sign it. With this document, the master declared his approval of the apprentice’s art, his trust in him, and his acceptance of the apprentice as part of his own artistic lineage. Receiving an ijazah was the greatest honor for a prospective calligrapher, signifying that he was now recognized as a “master” and could train his own apprentices.

The Tools Where Art Embodies: Ottoman Calligraphy Materials

The unique aesthetics of Ottoman calligraphy stemmed not only from the calligrapher’s mastery but also from the quality and meticulous preparation of the materials used. Calligraphy materials were a calligrapher’s most precious treasure.

Reed Pen, Soot Ink, and Ahar-Treated Paper

Reed Pen: The pen, the hand and soul of the calligrapher, was typically made from a hard and durable reed (kargı) grown in swamps. After being dried for months, the reed was shaped by the calligrapher with a special knife called a “kalemtraş,” and its tip was cut at a specific angle according to the type of script to be written (Thuluth, Naskh, etc.). Preparing the pen’s tip in this manner required mastery in itself.

Soot Ink: The ink used in calligraphy was generally known as “soot ink,” a permanent and shiny black ink. It was prepared by mixing soot, obtained from burning substances like linseed oil, beeswax, or pine resin, with Arabic gum. This natural ink would not fade over time and gave the paper a deep blackness.

Ahar-Treated Paper: Calligraphers did not use ordinary paper. The surface of the paper was coated with a substance called “ahar,” a mixture of egg white and starch, and then polished with an agate or glass tool called a “mühre”. This process made the paper’s surface smooth, allowing the pen to glide fluidly, preventing the ink from spreading, and most importantly, enabling easy erasure and correction of mistakes.

From Palace to Daily Life: The Place of the Calligrapher in Ottoman Society

In Ottoman society, calligraphers were not merely artisans but highly respected artists and intellectuals. The largest and most prestigious employer was undoubtedly the palace. Calligraphers working in the “Nakkaşhane,” attached to the Ehl-i Hiref organization within Topkapı Palace, prepared handwritten books for the sultan, drew tughras on edicts, and wrote inscriptions for the architectural structures of the palace.

However, the scope of calligraphers’ activities was not limited to the palace. Wealthy pashas, scholars, and merchants became significant patrons by commissioning books for their libraries or calligraphy panels to adorn their homes. Additionally, calligraphers with their own shops in and around Istanbul’s Grand Bazaar earned their living by writing amulets, prayer panels, or tombstone inscriptions for the public. The fact that many sultans (such as Bayezid II and Mustafa II) were themselves master calligraphers was the greatest indicator of the importance given to this art.

Brushes That Signed History: Calligraphers Who Left Their Mark at Topkapı Palace

Ottoman calligraphy has produced countless great masters throughout history. The works of many of these famous Ottoman calligraphers adorn the collections of the Topkapı Palace Museum today.

Şeyh Hamdullah (1436-1520): Referred to as “the Qibla of Calligraphers,” Şeyh Hamdullah revolutionized the art of calligraphy. He elevated the six fundamental script types (Aklam-ı Sitte) to their most mature aesthetic level and established a school (ekol) for all subsequent calligraphers.

Hafız Osman (1642-1698): He was the greatest follower and innovator of the Şeyh Hamdullah school. He brought a new breath to calligraphy, especially by standardizing the “Hilye-i Şerif” form (a panel describing the physical and moral attributes of Prophet Muhammad).

Mustafa Râkım Efendi (1757-1826): He was the genius calligrapher who brought the Sultan’s tughra to its most perfect aesthetic form. He is known for his mastery of the Celi Thuluth script and his compositional skill.

The Spiritual Depth of Letters: The Mystical Aspect of Ottoman Calligraphy

In conclusion, Ottoman calligraphy is not merely a product of an aesthetic pursuit. It is a mystical journey that seeks the spiritual depth believed to be hidden within letters, requiring patience and submission. For the calligrapher, holding the pen is an act of worship. Each letter is a reflection of divine beauty. The letter Alif symbolizes the oneness of Allah (wahdaniyyah); the letter Vav symbolizes the humility of a servant prostrating, reminiscent of a human in the womb. This deep symbolism ensures that what the calligrapher puts on paper is not just a text, but also a part of his own soul and faith. The unique letters we see on the walls and in the manuscripts of Topkapı Palace whisper the immortal echoes of this spiritual journey to us.

Frequently Asked Questions about Ottoman Calligraphy

What makes Ottoman calligraphy unique compared to other forms of Islamic calligraphy?

While sharing the same spiritual foundation, Ottoman calligraphy developed a distinct aesthetic refinement. Masters like Şeyh Hamdullah and Hafız Osman perfected the proportions of the Aklam-ı Sitte (the six primary scripts), creating a unique harmony and grace. The Ottomans also innovated specific forms, such as the tughra (the sultan’s imperial cipher) and the standardized layout of the Hilye-i Şerif, turning them into iconic artistic genres that are distinctly Ottoman.

Is it possible to learn traditional Ottoman calligraphy today?

Yes, the master-apprentice tradition (meşk) continues to this day, though it is rare. In Istanbul and other cultural centers, there are workshops and masters who teach the art using the same patient, repetitive methods. Learning requires immense dedication, starting with perfecting single letters for months, if not years, before moving on to complex compositions. It is a journey into not just a craft, but a spiritual discipline.

What is the spiritual meaning behind the letters in calligraphy?

In Ottoman calligraphy, letters are not just phonetic symbols; they are vessels of spiritual meaning. The letter Alif ( ا ), a single vertical stroke, represents the absolute oneness of Allah (Tawhid). The letter Waw ( و ), with its curved form, is often seen as symbolizing a human in prostration or a fetus in the womb, representing humility and dependence on the Creator. A calligrapher’s work is thus a form of meditation, an attempt to manifest divine beauty through the physical act of writing.