The Architect and Tragic Hero of the Tulip Era: Nevşehirli Damat İbrahim Pasha

While Ottoman history is often defined by conquest, the Tulip Era stands as a brilliant exception—a brief period when elegance reigned over war. The architect of this cultural renaissance was Damat Ibrahim Pasha, a visionary reformer who turned the empire’s face toward the West. Under his guidance, Istanbul flourished with unprecedented artistic vitality. Yet, the splendor he cultivated in his famous tulip gardens concealed the thorns of rebellion that would seal his tragic fate, making his story a chronicle of an era he both created and perished with.

The Birth of an Era: Damat İbrahim Pasha’s Rise and Vision

To understand the brilliance of the Tulip Era, one must first understand the vision of the man who created that brilliance. Nevşehirli Damat İbrahim Pasha was born into a modest family in Muşkara (present-day Nevşehir), far from the empire’s center. He entered the palace system from the lowest ranks, gradually rising through his intelligence, diplomatic skill, and diligence. The pivotal event that changed his destiny was his marriage to Sultan Ahmed III’s daughter, Fatma Sultan, making him a “Damat” (son-in-law) to the palace. This marriage not only gave him a title but also opened the way to the Sultan’s absolute trust and the highest echelons of the state.

In 1718, he was appointed Grand Vizier immediately after the Treaty of Passarowitz, which resulted in heavy territorial losses for the empire with Austria and Venice. This meant inheriting a ruin. However, İbrahim Pasha had the vision to turn this defeat into an opportunity. He realized that the era of expanding the empire through conquests was over, and that true power lay in science, art, culture, and stability achieved through diplomacy. His vision was to transform the weary warrior empire into an elegant, intellectual, and world-oriented civilization. This would be the first and most aesthetic step in the Ottoman modernization movements.

The Capital of Elegance and Innovation: Istanbul’s Transformation in the Tulip Era

With Damat İbrahim Pasha’s Grand Vizierate, Istanbul began to experience a transformation it had never seen before. The city’s atmosphere changed. Discourses of war and conquest were replaced by conversations about poetry, music, and art. The palace and the surrounding elites turned their faces towards Paris and Vienna, adopting Western lifestyles, fashion, and architecture. This period takes its name from the extraordinary interest in the tulip flower, the tulip festivals held, and the frequent use of tulip motifs in art. The tulip was the most elegant symbol of this new aesthetic understanding and joy of life.

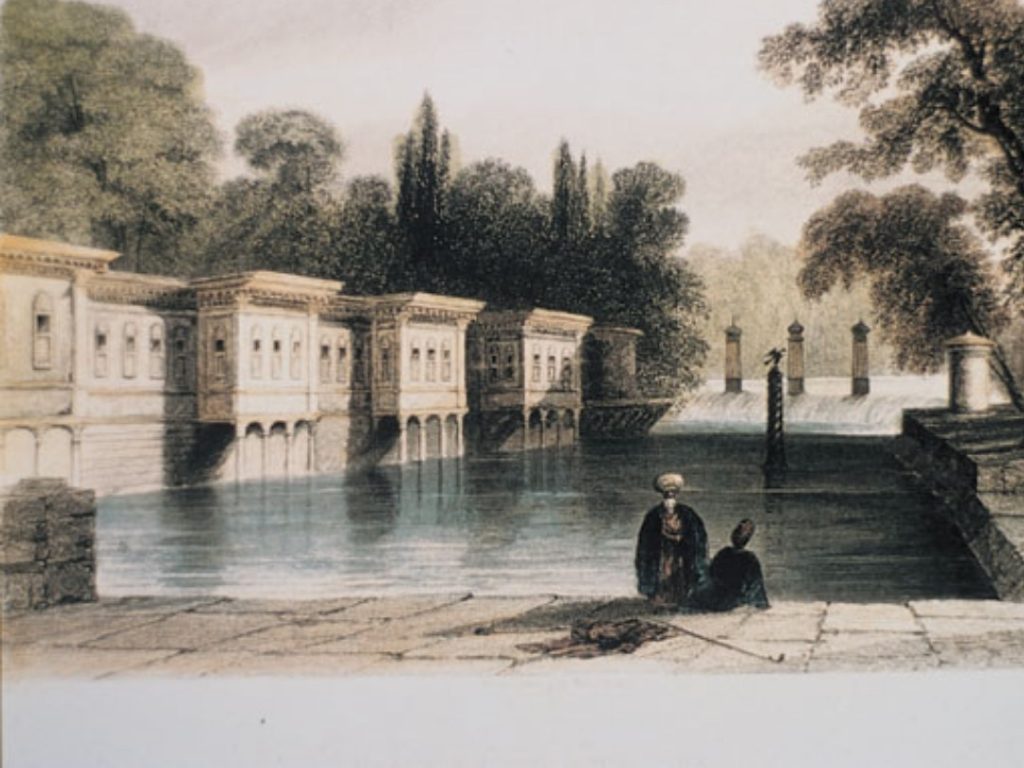

Sadabad: The New Stage for Palace Entertainment and Civil Architecture

The heart of this new lifestyle beat at Sadabad Palace and its surrounding gardens, built on the shores of the Golden Horn, by the Kağıthane Stream. Designed inspired by the French Fontainebleau Palace, it was a structure more civil, more human-scaled, and integrated with nature, unlike traditional Ottoman palace architecture. Sadabad was not just a palace, but a living space. It was surrounded by more than a hundred small mansions and kiosks (“Sadabad Mansions”) built by other statesmen and the wealthy.

This place became the scene for the legendary entertainments of the Tulip Era. At night, lantern processions called “Çırağan Sefaları” were held, and the gardens were illuminated with thousands of oil lamps and candles. Narratives about candles being placed on the backs of tortoises and paraded around the garden reflect the era’s pursuit of fantasy and aesthetics. In these entertainments, immortalized in the verses of the famous poet Nedim, poems were recited, music was listened to, and elegant conversations took place. Sadabad was the new center of art and culture in the Ottoman Empire and the embodiment of Damat İbrahim Pasha’s vision.

From Printing Press to Tiles: Bold Steps in Art and Science

The Tulip Era was not just about entertainment and pleasure. Under Damat İbrahim Pasha’s patronage, significant scientific and artistic advancements were made that would affect the future of the empire.

Establishment of the Printing Press: The most revolutionary step of the period was the establishment of the first Turkish printing press by İbrahim Müteferrika in 1727, with the full support of Damat İbrahim Pasha. Despite objections that calligraphers would lose their jobs and that printing religious texts was sinful, the press began operating due to the Pasha’s insistence and a fatwa from the Sheikh al-Islam. Although initially only non-religious books (history, geography, dictionaries) were printed, this was a giant step towards the dissemination of knowledge and modernization.

Revitalization in Art: During this period, all branches of art, especially miniature painting, experienced a revitalization. The famous painter Levnî stood out with his elegant and realistic miniatures reflecting the spirit of the era. New workshops were established for tile art, and elegant fountains (like the Ahmed III Fountain) and public water dispensers showing Baroque influences were built in architecture.

Scientific Curiosity: Damat İbrahim Pasha sent ambassadors to Paris and Vienna to follow Western scientific and technological developments. Yirmisekiz Mehmed Çelebi’s Paris Sefaretnamesi (Embassy Report of Paris) became one of the most important works introducing Western civilization to Ottoman intellectuals. Additionally, a translation committee was formed to translate important works from Western languages into Turkish.

Thorns Behind the Tulip Gardens: Social Reaction and the Footsteps of Rebellion

Behind the bright and innovative face of the Tulip Era, a growing social discontent was accumulating. This luxurious and Western-style life enjoyed by the palace and its surrounding elites was seen by a large segment of the public as extravagance, debauchery, and a deviation from religion. New taxes imposed to finance the enormous expenses for the entertainments at Sadabad further increased the public’s reaction, who were already in difficult economic circumstances.

The deep chasm between this luxurious life and the poverty of the people, further instigated by conservative ulema and some dissatisfied statesmen, became a ticking time bomb. Damat İbrahim Pasha and his circle began to be seen by the public as an elite group that had forgotten the state, caring only for their own pleasure. The built mansions were perceived as symbols of extravagance, and Western customs adopted were seen as symbols of corruption.

Tragic End: The Patrona Halil Rebellion and the Close of an Era

On September 28, 1730, this accumulated anger finally erupted. A small group of rebels led by Patrona Halil, a former Janissary and bath attendant of Albanian origin, started their action in the Grand Bazaar and quickly gained the support of the public, merchants, and soldiers, turning into a massive rebellion. The Patrona Halil Rebellion was a bloody popular movement that brought an end to the Tulip Era. The rebels burned and destroyed the mansions at Sadabad and everything they considered luxurious.

The rebels demanded the surrender of Grand Vizier Damat Ibrahim Pasha, holding him responsible for the era’s perceived excesses. Unable to suppress the revolt and facing dethronement, Sultan Ahmed III was forced to concede. On the night of October 1, 1730, Damat Ibrahim Pasha was executed, his death marking the brutal end of the Tulip Era itself. His body was handed over to the mob and paraded through the streets of Istanbul. Shortly after, the Sultan who had empowered him was also forced from the throne.

Legacy: Traces Remaining from Damat İbrahim Pasha to the Present Day

Nevşehirli Damat İbrahim Pasha, despite his tragic end, was a statesman who left deep marks in Ottoman history. He was the first great reformer who turned the empire’s face towards the West. With the printing press he established, the translations he commissioned, and the artists he patronized, he sowed the seeds of subsequent modernization movements. The elegant fountains and civil architectural examples built during the Tulip Era still contribute to Istanbul’s aesthetics today. His story is a tragic example of how fragile an innovative vision can be when not balanced with social realities and public sensitivities.

Frequently Asked Questions about Damat İbrahim Pasha

Why is the period called the “Tulip Era”?

The era gets its name from the immense popularity and cultural significance of the tulip flower among the Ottoman elite. Under İbrahim Pasha’s influence, lavish tulip festivals were organized, and the tulip motif became a dominant symbol in art, poetry, and architecture, representing the period’s focus on elegance, beauty, and the pleasures of life rather than conquest.

What was Nevşehirli Damat İbrahim Pasha’s most important legacy?

While the elegant architecture and cultural renaissance are memorable, his most revolutionary legacy was co-sponsoring the first Turkish-language printing press in the Ottoman Empire in 1727. This act, overcoming significant conservative opposition, was a monumental step towards the modernization and dissemination of secular knowledge, sowing the seeds for future reform movements.

Was the Patrona Halil Rebellion solely a reaction to the era’s luxury?

While the lavish lifestyle of the elite was the visible trigger, the rebellion had deeper roots. It was fueled by significant economic hardship among the common people, new taxes levied to pay for the court’s expenses, political jealousy from rival statesmen, and a conservative backlash against the perceived Westernization and deviation from traditional values. The Tulip Era’s splendor created a dangerously wide gap between the palace and the public.