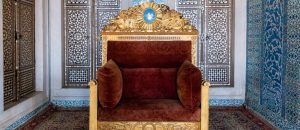

Topkapi Palace was one of history’s most powerful centers, not only with its marble courtyards, priceless treasures, and magnificent pavilions, but also with the written texts produced within its walls that shaped the destiny of an empire spread across three continents. These texts, namely kanunnameler (codes of law) and fermanlar (imperial edicts), were the sultan’s will put to ink, regulating every aspect of life from the appointment of a governor to a peasant’s tax debt, from an army’s campaign to the construction of a city. Laws and edicts in the Ottoman Empire were not merely legal documents; they were meticulously crafted works of state art that carried the empire’s understanding of justice, order, and power from the gates of Vienna to the deserts of Yemen. This article will trace the journey of this written power, which began under the dim domes of the Divan-ı Hümayun (Imperial Council) and concluded at the desk of a qadi (judge) in the empire’s remotest corner.

The Written Power of the Empire: What are Kanunname and Ferman?

These two concepts, forming the foundation of the Ottoman legal system, represent different forms of the empire’s written power. Although related, there is a fundamental functional difference between them. A kanunname is a comprehensive collection of laws that are general, abstract, and long-lasting, bringing together rules on a specific subject or the entire state organization. It can be likened to modern-day constitutions or criminal and civil codes. One of the most famous examples, Fatih Sultan Mehmed’s Kanunname-i Al-i Osman, was a fundamental text regulating the state organization, protocol, and criminal law.

A ferman, on the other hand, is a specific and concrete command given by the sultan regarding a particular subject, person, or event. Decisions such as an appointment, a tax exemption, the granting of a privilege, or the initiation of an investigation were announced by ferman. If a kanunname was a law book, a ferman was a single page ordering the application of that book to a specific situation. Each ferman represented the absolute will and executive power of the sultan, a command that had to be immediately implemented.

Where Decisions Were Made: The Divan-ı Hümayun and the Process of Law Formation

The birthplace of the empire’s written power was the Divan-ı Hümayun, which convened in the Kubbealtı (Under the Dome) in the second courtyard of Topkapi Palace. This was the highest administrative and judicial body of the empire. When a new law was needed or an existing law required amendment, the matter was first discussed here. Decisions of the Divan-ı Hümayun were shaped through lengthy discussions chaired by the Grand Vizier, with the participation of the state’s highest officials such as the Kazaskers (justice), Defterdars (finance), and Nişancı (bureaucracy and law).

The Ottoman legal system was founded on two main pillars: Sharia Law (based on Islamic law) and Customary Law (based on traditions and the sultan’s will). Kanunnameler created in the Divan fell within the domain of customary law but could never contradict Sharia law. While the Kazaskers supervised the compliance of decisions with Islamic law, the Nişancı controlled their conformity with existing customary law and state traditions. This complex process ensured that laws possessed both divine and worldly legitimacy.

From the Nişancı’s Pen to the Sultan’s Seal: How Was a Ferman Written?

The transformation of a decision made in the Divan into an official ferman or kanunname text required an exceptionally meticulous bureaucratic process. The central figure in this process was the Nişancı, who, by virtue of his duties, was the state’s chief legal officer and bureaucrat.

The process of writing a ferman typically unfolded as follows:

- Decision: The matter was discussed and decided upon in the Divan.

- Draft Preparation: Scribes attached to the Divan prepared a draft of the decision.

- Nişancı’s Review: The draft text was submitted to the Nişancı. The Nişancı reviewed the text in terms of both legal terminology and the state’s official style, made necessary corrections, and finalized the text. This ensured that the text was in compliance with laws and traditions.

- Drawing the Tughra: After the text was finalized, the most critical stage was reached: the drawing of the tughra, which was the heart of the document in terms of the sultan’s tughra and its meaning. The tughra, the sultan’s signature and the state’s emblem, was skillfully drawn by the Nişancı or officials under his supervision on the uppermost part of the ferman. The tughra was a complex calligraphic composition containing the sultan’s name and titles, ending with the prayer “always victorious”. It was a sacred seal symbolizing that a document carried the sultan’s will and was an irreversible command.

After these stages, the ferman would be dispatched to the relevant person or institution.

From Land to Army: The Effects of Kanunnameler on Social Life

Kanunnameler were not merely texts confined to paper; they were a body of rules that fundamentally shaped the empire’s social, economic, and military structure, touching the lives of all segments of society. This impact reached its peak particularly with the laws of Suleiman the Magnificent; his epithet “the Lawgiver” (Kanuni) derives from his role in law-making.

Regulation of the Agricultural and Tax System

Agriculture was the backbone of the Ottoman economy. Kanunnameler clearly defined how much tax (öşür) a farmer (reaya) in the remotest corner of the empire would pay to the state, which crops they could cultivate, and their rights against the timariot (timarlı sipahi) who held the land. This prevented arbitrary taxation by local administrators, guaranteed state revenues, and aimed to ensure social justice by preventing the oppression of the reaya. Special kanunnameler were issued for each newly conquered region to establish a fair tax system suited to the local conditions of that region.

Rules of the Military Structure and Timar System

The timariot cavalry (tımarlı sipahiler), the most numerous and important force of the Ottoman army, were organized within an ingenious structure called the Timar System. The entirety of this system was regulated by kanunnameler. The revenues from the land granted to a sipahi, called “dirlik” or “tımar,” covered his livelihood and the expenses of the armed soldiers called “cebelü” that he was obliged to provide to the state in times of war. Kanunnameler specified in minute detail how many soldiers a sipahi had to maintain in exchange for a certain income, what penalties he would incur if he did not participate in campaigns, and how he should treat the peasants on his land. This was a legal infrastructure that enabled the maintenance of a massive army without expenditure from the treasury and kept it ready for war at all times.

Orders Reaching Three Continents: The Role of Fermanlar in Imperial Administration

While kanunnameler formed the general framework of the state, fermanlar were the orders that provided the blood circulation within this framework, governing the empire moment by moment. A ferman could order a governor in Egypt to build canals to prevent the flooding of the Nile River, instruct a qadi in Buda to resolve a dispute between two merchants, or grant a Venetian merchant permission to trade in the port of Istanbul. These written commands were delivered to the farthest reaches of the empire by messengers (ulaklar), taking weeks or months to travel. Wherever a ferman reached, it meant the sultan’s authority reached. This system made it possible to govern millions of people speaking different languages and belonging to different religions, from a single center, Topkapi Palace, through the power of the written word.

Written Legacy: Why Are These Texts Important for Understanding the Ottomans?

These kanunnameler and fermanlar written in Topkapi Palace are invaluable treasures for today’s historians. They are first-hand sources not only about laws and edicts in the Ottoman Empire but also for understanding the empire’s mindset, priorities, and daily life. Through these texts, we can see how the Ottomans defined justice, managed the economy, sought solutions to social problems, and understood the administrative genius that held diverse cultures together. They are immortal proofs of how an empire was governed not only by the sword but also by a righteous pen and an unwavering sense of order.

Call to Action: Explore our comprehensive travel guides to Topkapi Palace and other cultural treasures of Istanbul at destinationturkey.tr.

Tags: Ottoman Legal System, Ferman, Kanunname, Topkapi Palace, Divan-ı Hümayun, Nişancı, Sultan’s Tughra, Suleiman the Magnificent, Ottoman History, State Organization.